StoryCraft

Writer’s Groups and Wimpiness

I’ve taken part in two distinct types of literary community. In the first, people come together, usually at an establishment specializing in $8 variations on Folgers pre-mix, and exchange opinions on each other’s masterpieces. In the second, hundreds of people don’t come together in front of their computer screens or mailboxes to soak up the great wisdom sprinkled from brown magazines and the vast expanses of the netdom.

On the surface, these two groups do indeed share commonalities. They both emphasize sharing, criticizing and improving literary works through the honest exchange of opinions. Both seek to support writers in their quests to finish that book/get published/single-handedly kick Stephen King off the bestsellers list.

What they do not share is outlook. Look, for example, at this cover of Writer’s Digest.

First, we’ve got a stirring beige theme because beige is the color of passion. Then we see a smiling, elderly woman with no obvious connection to the rest of the cover because that is evidently the sort of person who would be Shakespeare if only they had seven ways to use inspiration. Then, of course, this wildly innovative and avant garde cover design promises to help you, too, get creative.

Look inside and you will find advice on such pressing matters as “gaining the courage to show your work to others.” There will be help for those too afraid to “deal with being in a classroom again” and great tips for overcoming the dread we all feel (we do?) before starting a new literary project.

As with all great pieces of literature, you will find within the hallowed pages of Writer’s Digest no profanity, no mention of unmentionables, no low-brow references to pop culture (especially the horrid vulgarity that is anything newer than 1961), no politics, no revolution, no sex, no philosophy or violence. In short, Writer’s Digest has lots of stuff which could in no way offend the target audience of conservative, house bound women whose senses of humor sit quietly desiccating beneath obsessively cleaned living room rugs.

I’ve found a similar environment with most of the online critique groups I’ve tried—the same fear of going somewhere new, fear of experience, fear of failure, fear of everything. The biggest difference is that, shielded by anonymity, the beige crowd feels more empowered to exercise its censorious ninnyism. Never write a compelling villain because doing so makes you, the author, morally suspect as well. Never write about people from other cultures because that’s insensitive, but also always write about people from other cultures because that’s inclusive. Be patriotic because that makes people feel nice but also don’t be patriotic because it causes divisions. Avoid, at all costs, anything real or meaningful in an online critique forum because, as we all now, the best writers are always the most conventional.

This is not to say that online critique groups or writers’ magazines are bad. They are usually better than nothing and indeed, you can learn from both. But they are very, very limited and prone to what I shall describe as, for lack of a better word, intellectual constipation.

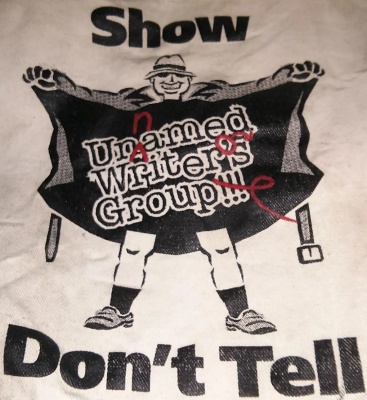

By contrast, consider this tote bag created by the Unnamed Writer’s Group (now called High Sierra Writers). The proceedings were, as you might infer, lively.

We sat in coffee shops or somebody’s front room and talk about the biggest douchebags we’ve ever met. We swap horror stories about dates, we talk shit. Group leaders have hot flashes and narrate menopause for our edification. Old women try their hands at gangster rap. Yours truly comes jacked up on opiates three hours after an appendectomy and nobody blinks.

Our literary focus knows no boundaries. Do you want to write a more compelling examination regarding racially defined loss-of-culture? Here to help. Do you want to find out how a zombie would pull apart its victim? Bring it on. Do you want to write the most hilariously inept sex scene ever in order to satirize a Kardashian? Let’s bust out the thesauri. No judgment, no fear, no pearl clutching.

And this leads me to my second observation about in person and online literary communities. The published authors I’ve come across in literary communities are overwhelmingly, hugely active in the face-to-face sphere.

***

When I listen to struggling writers — writers who never finish the book, never get the article published, give up after 14 pages — they always seem to mention problems with inspiration. “I just don’t have any ideas.” “I’ve run out of inspiration.” “I can’t find my muse.”

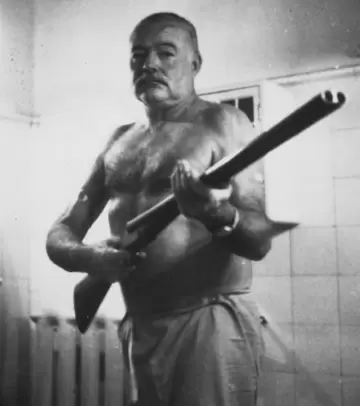

Ernest Hemingway battled writer’s block once. He busted a cap in that ass.

Where, then, does inspiration come from? Let’s look first to Ernest Hemingway because he’s famous and liked to get his picture taken.

When Mr. Hemingway was low on inspiration, he responded by killing grizzly bears. No, really. He went out and hunted bears. He also volunteered as an ambulance driver in WW1 where, upon receiving severe shrapnel wounds to both legs, he nonetheless carried a wounded Italian soldier to safety. After the war he moved to France, cavorted with Picasso, and drank psychoactive spirits. He watched the burning of Smyrna in person, ran with the bulls and had a lot of adulterous affairs. Shortly after Hemingway’s father committed suicide, he suffered a compound arm fracture that healed with the use of transplanted kangaroo tendons. He caught dysentery in Africa, covered the Spanish Civil War and wrote a play whilst enduring aerial bombardment. Ernest Hemingway, it seems safe to say, did not lead a boring life and thus, in pursuing all these dangerous and amazing experiences, supplied himself with a nearly bottomless well of inspiration from which to draw his fiction. But surely he is an outlier among successful writers, right?

Watch out everybody, he’s feeling crazy, he’s feeling wild, he might even cough without saying excuse me.

Let’s look at my favorite living author, Mohsin Hamid. His appearance is certainly more like the “hunched over a keyboard, shut in, all-my-friends-think-golf-is-an-extreme-sport” writerly stereotype.

He’s not as macho as Hemingway — Ivy League education, rich parents, only one marriage and an extended family with which he’s seemingly on good terms.

But here as well, Mr. Hamid has a deep well of experience. He’s hung around with Toni Morrison and bounced from Asia to Europe to America and back to Asia. He’s been to theaters barricaded against terrorist attack and had cause to muse on the efficacy of plate glass windows as improvised anti-personnel weapons. He made a living as a corporate shark in New York and, he has heavily implied, had first-hand experience in Pakistan’s drug underworld. He writes about religion and identity in a society where blasphemy is a thing, and a thing that sometimes ends in ritual decapitation. His, as well, has not been a boring life.

And I can extend this list almost indefinitely. Jane Austen spent her entire life browbeating public idiots and ignoring the things women weren’t supposed to do. Dante was a soldier and politician who, in a stroke of luck, officially had his death sentence rescinded in 2008. Melville killed whales with his hands. Marlowe was assassinated by rival spies. Are you noticing a pattern? Wimps and bores are noticeably thin on the ground when it comes to great writers.

As writers we are, on a basic level, taking our (hopefully) well-developed observational abilities and using them on experiences. This takes courage, courage to seek out these frightening, painful and dangerous experiences. Courage to say our minds with the full knowledge others might hate us for our opinions. Courage to, metaphorically, strip naked and expose our shameful/dark/scary sides to public scrutiny.

You can’t do these things by reading brown magazines in your front room. You can’t do these things hidden anonymously in an online critique group. That’s why writers who get out of the house and face a real-life community do better — they aren’t cowards.