StoryCraft

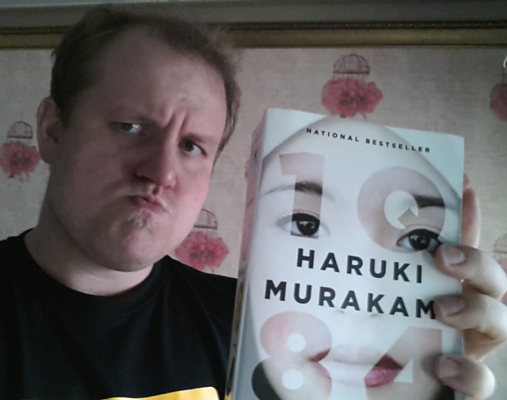

Exuberance over Pretense, An Examination of 1Q84

I should say first that I would recommend this book to almost anybody. 1100 pages of I’m not sure what, but 1Q84‘s endlessly entertaining, the pacing (somehow) works and the world building is masterful. Haruki Murikami’s imagination seems to operate in the same, fevered, delirious and warped way that normal people only experience while dreaming after a period of sleep deprivation.

But what I can’t honestly say is that 1Q84 is particularly well characterized. Aomame, the main female character, seemed to me more a compilation of “action girl” fantasies than a real person. Tengo, the male lead, is likewise the sort of loser-ish dude with a crappy apartment and unexceptional looks who, somehow, just can’t seem to stop getting laid. The way ladies treat him, to say the least, strains my willing suspension of disbelief. The third, sort of main character is more believable than the other two and yet Murakami never ceases to tell us, essentially, “no matter what you see him do, it’s important for you to remember that Ushikawa is bad.” This doesn’t even get to the large swaths of long-winded, not-at-all realistic expository dialog. If I had a dollar for every time a character tells Aomame “I know you are careful and disciplined” right before she does something careless and undisciplined, I’d have enough money to go on a three or four hour junk food binge.

Dangling plot threads, likewise, tickle the literary nose with every sniff. A major character gets resurrected by the eldritch abomination right before the end of the story and does &emdash; nothing. Another just vanishes for no particular reason. Tengo may or may not have spent a night with his reincarnated mother while she rubbed him with her pubic hair. Then there’s the elaborately foreshadowed betrayal of a main character that Murikami seems to forget about three quarters the way through. And we never do figure out what the “little people” want.

The writing itself isn’t so hot either. Murakami repeats himself like a person who repeats himself like a person who repeats himself repeatedly, repeating repetitions until you wish he’d just figure out a synonym. The register of the prose, as well, drifts back and forth between elementary school basic and attractively bloated. Murakami consistently does to the “show don’t tell” rule what Texans do to toilette paper after a chili cook-off. So why on earth would I recommend this door-stopping, inconsistently characterized and sometimes clunky book?

***

Ray Bradbury’s name floats around the internet connected with approximately 7X10^49 articles about writing. I’m not sure how this happened, because although Bradbury’s a lot of fun, I don’t know of anybody who considers him a master stylist. Regardless, the thing that keeps popping up first on those “Bradbury spritzes you with his literary genius lists” is always some variation on or derivative of this:

“Zest. Gusto. How rarely one hears these words used. How rarely do we see people living, or for that matter, creating, by them. Yet if I were asked to name the most important items in a writer’s make-up, the things that shape his material and rush him along the road he wants to go. I would only warn him to look to his zest, see to his gusto.”

If I interpret this correctly, Mr. Bradbury wants his fellow writers to spend a lot less time agonizing about subordinate clauses and more time blowing up space aliens with awesomeness cannons while giving true love’s first kiss and riding a crocodile. I’m sure this advice horrifies my beige friends in the online critique group of infinite frumpiness, not to mention the admirers of “eloquence” Mark Twain had so much fun with. And I’m reasonably sure the literary luminaries being made fun of here disagree, but who cares?

Zest means ambition, even if checkered with failure. Gusto makes us think of unselfconscious glee, of deeply and profoundly not giving a fuck. Bradbury’s ideal means grabbing hold of the theme or story or idea or nightmare or demon or fantasy that keeps us awake at night and getting it on paper&emdash;however imperfectly. It means writing with passion, with a meaning made as plain as possible, even if it’s not entirely elegant. It looks a lot like this:

“If you can love someone with your whole heart, even one person, then there’s salvation in life. Even if you can’t get together with that person.”

— Haruki Murakami 1Q84

It looks nothing like this:

“It simply dived straight down the throat, with the mouth closing behind it so quickly that the whole event seemed as if it hadn’t actually happened outside my imagination. In fact, it seemed not to happen at all, but, rather, suddenly, to have happened.”

— Pulitzer Prize winning author Paul Harding’s immensely pretentious and boring novel Tinkers.

***

Murakami is one incredibly imaginative dude. He runs over genre conventions with exuberance—fantasy characters in cosmic horror settings, Orwellian dystopia and love at first sight, the creeping influence of casual magic in what at first seems a realistic story, cat town, a second moon, portal sex…

Gusto, it seems, covers up a lot of sins.